[ad_1]

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — On the January day three years ago that Kgomotso Tjie found out he’d made it into an elite South African university, he logged onto his Facebook page and typed a message with shaking hands. The moment he’d worked toward all his life had arrived.

“I thank God for granting me the desires of my heart,” he wrote.

For Tjie, the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg was the promised land, evidence that being poor and black was no longer a barrier to success in South Africa. Born in a rural township some 400 miles northeast of Johannesburg, he'd started believing that hard work and smarts really might be enough.

It had been a lonely odyssey to get there. At his all-black high school, more girls get pregnant each year than students make it to university, and guidance from teachers on how to apply to university had been minimal. Stumbling through a stash of application forms alone at a local library, Tjie had been stumped by even the most basic bureaucratic questions. He’d never encountered officious phrases like next of kin. Back home, his mother, who sold vegetables by the roadside to help make ends meet, couldn't offer much practical advice.

Just a quarter of Tjie’s year group at the state-funded M.L. Nkuna High School got the grades required to get into university that year, reflecting the enrolment rate of black students across public schools in the country. Tjie was one of the lucky ones who got the grades and could scrape together the money for fees to actually enrol. But once he got to Wits — as the university is known to students and teachers alike — he found himself plagued as much by self-doubt as financial constraints.

“I never fool myself into thinking because I’m here — because I left most of my peers in townships and villages — I’m a ‘better black.’ The struggle doesn't end just because I made it to Wits,” he said quietly one afternoon at the end of last year, as we sat in a terraced amphitheater overlooking the campus’s Olympic-size pool.

It’s a reality that gets to the heart of a political battle defining this generation of South Africans. Those who came of age in a country unshackled from the white-minority rule known as apartheid have found themselves confronting a painful question. What does it mean to be black in a country that still confers advantages on white people in every walk of life, even now, more than two decades after the end of minority rule?

The first rumblings of a movement that was to sweep across campuses began back in March 2015, when a black student threw a bucket of shit over a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, a proudly racist British imperialist and mining magnate, which looked down over the main square at the University of Cape Town. That act of defiance had an elegant symmetry to it: Rhodes used to force his black miners to have the contents of their bowels examined to prevent them from stealing diamonds. Students called for the removal of the statue, launching a campaign known as “Rhodes Must Fall.” Critics saw it as an attempt to “erase history,” an irony not lost on those fighting to get rid of a statue celebrating a bigot who saw Africa as little more than a plundering ground for white advancement.

Such protests had quietly simmered for years in universities largely attended by black working-class students, but this was the first time since apartheid ended in 1994 that formerly whites-only colleges were involved — and the media began paying serious attention. The Rhodes Must Fall fight for racial justice soon echoed across the globe from Princeton to Oxford to Edinburgh, as students began calling out universities for their roles in harboring vestiges of white supremacy.

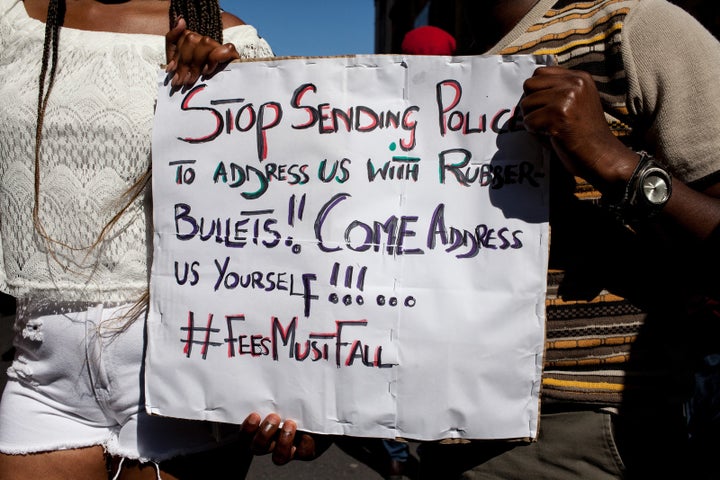

In South Africa, talk moved from the psychological ways in which nonwhite students remain disenfranchised to the practical. Rhodes Must Fall morphed into “Fees Must Fall” as black students demanded “free and decolonized” education, alongside calls for better conditions for poorly paid black workers employed by universities. Protest movements led by young black students flared across formerly white campuses, triggering a martial crackdown by the state. Week after week, heart-stopping clips emerged of police and private security swarming onto university grounds and engaging students in tense face-offs.

The wreckage of the year included university buildings set alight, more than 800 protesters arrested, and hundreds showing signs of post-traumatic stress. Two students lost their lives. The government increased bursary funding for those hardest hit, but little was actually resolved. With fees now raised in “Ivy League” universities like Wits, the threat of more protests, and perhaps ultimately more deaths, looms over this academic year.

In other words, post-apartheid rule papered over the gashes wrought by white minority rule with a so-called “rainbow nation” band-aid. But that is unraveling, and what happens this year will reveal yet further the depths of those wounds.

Kgomotso Tjie is grabbed by police at a protest on September 21, 2016.

Alon Skuy/The Times / Getty Images

At 22 years old, Tjie is baby-faced and doe-eyed, with a voice that remains soft even when he’s talking about crushing experiences — which, three years into life at Wits, is often.

This was supposed to be a new world, one in which his parents need no longer lie awake in their corrugated iron–roofed home feeling that, no matter how hard they try, it will never be enough for their son. Tjie, at least, out of their four children, had made it out of the townships. But reality quickly began to chip away at this mirage.

Which is why he sometimes avoids his parents when they call him from home. He doesn't know how to explain to them that daily he’s reminded of the fact he is temporarily inhabiting a space that was never meant for people like him — not just black, but poor too — and that, as a result, he constantly feels like he’s there on borrowed time.

There were the gut-wrenching moments that confront every black person. Like the October afternoon when the police had pelted him and other protesters with tear gas, and he’d rushed to shelter in another building. Two white students dashed in ahead of him. When he reached the entrance to safety, Tjie realized a man was blocking his way.

“Where’s your student card?” he recalled the man asking him.

He hadn’t asked the white students.

Sipho Mpongo

What shook him even more was when he recognized the man as a lecturer.

Later, reflecting on it, Tjie spoke with a resigned calm. “White people aren’t seen as part of this thing, as dangerous.”

When he first arrived at college, Tjie’s Facebook posts were peppered with references to being a “proud Witsie.” Outwardly, he knew it was a monumental achievement for someone who’d clawed their way through rural poverty and a broken public school system. But self-doubt was a constant internal soundtrack. He felt more at home joking around with the university cleaners — “They're our parents,” he said of them — than with most of his fellow students.

He knew what it was like to wake up with stomach cramps from hunger, because he couldn't afford a fridge and was often too tired to cook; his classmates were more likely to be fretting about morning rush-hour traffic. “Our situations,” he said of the latter, “are too different — you can’t compare two things that aren’t even the same.”

As he struggled through his first year, he found camaraderie in a group of black activists marching against the high price of university accommodation. Here were people who saw the world through the same eyes. If you’re born into a black household — as 80% of South Africans are — your average income is six times lower than that of a white household, meaning student fees of up to 108,000 rand ($7,922) disproportionately affect families like Tjie’s.

And, more than once, he’d thought of quitting university altogether — which some 50% of black students do in their first year. “When I first came to Wits, I almost dropped out and ran away home. You write the tests. You try by all means. But the struggle never ends.”

But his family back home was looking up to and depending on him. His elder sister, a graduate unable to find a job. His brother, who had not dared rack up the debt university would bring. His father, who'd come out of retirement to help scrape together money for his fees.

And he’d had high hopes himself. He’d grown up in Mpumalanga, in a farming community that also provided a steady stream of cheap labor to nearby luxury safari parks. As a kid he’d idolized his uncle who was a traffic cop. “He would drive, like, a better car. That’s what I saw each and every day, him living a better life.”

Education was his ticket to one day owning a car, to having money to help out his family. He'd staked everything on it. “I need to do better for my family because they’re all looking to me,” said Tjie.

“My friend yesterday had two rubber bullets. One next to the eye, and one in the leg. How am I gonna concentrate?”

Wits ripped him from the quiet rural life he’d always known and plunged him into the ever-hungry mouth of capitalism in Johannesburg. It was there he began to see clearly how the world worked, starting with the realization that his uncle, the cop who drove a battered car, wasn’t really such a big somebody. “When I came here I realized that no, that’s not life.”

He learned that a school uniform had been a blessing if all the clothes you had barely filled a tiny wardrobe. “Saturday, you’re happy you don’t even come to campus, and study in the room because they will see you wearing exactly the same thing.”

At Wits, he learned how to type properly for the first time.

And he learned that dreams were scaled firstly according to the colour of your skin, then the size of your bank account. “Growing up in Mpumalanga, the people you see who are successful are teachers, nurses. They drive when I walk every day — and you think that’s success. But when you come here you see white people,” he said, then sucked in air and held it for a long moment.

Somewhere along the way, everything became overwhelming; self-doubt morphed into self-sabotage. Adopting a phrase in Tswana, his language, as a mantra — ku rila a swi pfuni, which means, “crying doesn’t help” — he said he saw no point in asking his lecturers for help.

His grades began to slip, and with them the possibility of renewing a scholarship that depended on him getting at least 60% pass marks.

What needled him most, though, were the casual, everyday incidents he couldn’t quite pin down to his skin color, but neither could he shake off the feeling that’s what they were about. Like in class, after pairing up with white students. “After submitting a project or whatever, you don’t know each other any more. Tomorrow, hey—,” he mimed waving at someone, “they take out their phones to try and pretend they didn’t see you.”

For Tjie, who grew up in an all-black township, navigating race was an exhausting, constant undertow.

It came as a painful shock when the university insisted on preparing for exams in November even as protests raged around them. What he was fighting for, he realized, was abstract to most of his white peers. “My friend yesterday had two rubber bullets. One next to the eye, and one in the leg. How am I gonna concentrate?” he asked.

Then when he went to classes, feeling depressed, a white lecturer encouraged students to “take back Wits” from those who were protesting. “He said ‘take back.’ What does ‘take back’ mean? It means you owned it, right? It’s like we stole the thing away so they’re taking it back because it’s theirs.”

And it was the reason he stopped reading newspapers or online news. “You try by all means, but as a black protester, you’re still a hooligan. The media just keeps saying we’re hooligans.”

A few hours after we first spoke, Tjie sent me a message. He thanked me, politely, for talking to him. Since then, though, he’d been pacing around. “After the conversation we had, I had so much anger and I know it will not change the situation,” he wrote. He wouldn’t be able to talk with me again. Each minute of an interview with me meant twice that long dwelling on his painful reality later.

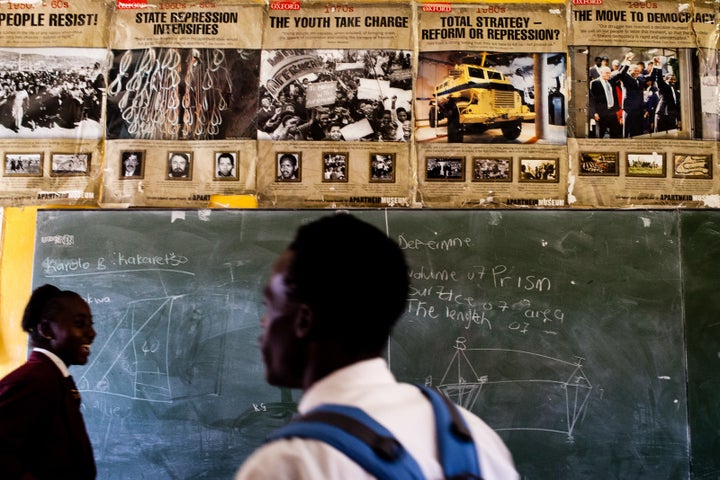

A history class room at a high school in Soweto, Oct. 2016.

Sipho Mpongo for BuzzFeed News

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Hopes had been so high when the country became a non-racial democracy that those born after the end of apartheid in 1994 were given a nickname full of promise: the born-frees.

Even now it’s hard to conjure the full horrors of apartheid.

Segregation had long existed in colonial South Africa, but in 1948 the all-white National Party enacted a system designed to keep nonwhite throats under white boots. Apartheid, the law of the land, was the separation of races — divided into whites, blacks, Indians, and “coloreds” (members of South Africa’s unique mixed-race heritage). A person’s political, civil, and economic rights — or lack thereof — were dependent wholly on which classification they fell into.

Divide and rule was used to devastating effect. The infamous pencil test — whether someone’s hair was curly or “black” enough to hold a pencil — was so arbitrary and imprecise it meant members of the same family could be forced apart. Some colored people sought to “go white” to improve their own lot in life — at the cost of being unable to see or talk to family or friends who weren’t willing or able to make the leap.

Literally meaning “apart-hood” in Afrikaans, apartheid went even further than the deprivations of Jim Crow in the US. Not unlike the far-right groups ascending in the US today, there was a yearning for a “pure” white nation. Black South Africans were effectively stripped of citizenship and forcibly sent to “Bantustans” — black homelands — so the government could achieve a white majority in “true” South Africa, the almost 90% of land reserved for the white minority. Nonwhites had to carry passes at all times, which determined where they could move around.

Grand apartheid dictated that black people were penned into townships, allowed to enter white areas for labor and domestic work only on designated buses. Petty apartheid was the sign that greeted workers, on return to their townships, saying, “CAUTION: BEWARE OF NATIVES.”

A few years after instituting apartheid, the government gave up the pretense that separate facilities had to be equal, and passed a law to that effect. The result: Inferior black-only buses took black students to inferior black-only schools. Inferior black-only ambulances took black patients to inferior black-only hospitals, and when black people died after receiving inferior treatment, they were buried in inferior black-only cemeteries. Toilets, swimming pools, bars, restaurants, churches, bridges, cinemas, beaches, parks, benches, railway cars, drinking fountains — all were separate and unequal.

The aftermath of a burglary at Madibane High School.

Sipho Mpongo For Buzzfeed News

[ad_2]