[ad_1]

In October 2002, as 80 people attended a Friday night service at the Temple Beth Israel synagogue in Eugene, Oregon, rocks etched with swastikas crashed through the stained-glass windows. Locals remembered it as the most shocking hate crime in the state in years — even more brazen than one eight years earlier, when rifle rounds pierced the empty temple’s doors and walls. For the 2002 attack, five members of a white supremacist group were convicted. The most prominent among them, Jacob Laskey, was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

When Laskey was released in late 2015, he returned to a society that seemed more receptive to racist ideology than at any point in at least a generation. Across the country in recent months, several mosques have burned, scores of Jewish centers have received bomb threats, and at least three brown men have been shot, one fatally, by white men who demanded that they leave the country. In Salem, Oregon, earlier this month, a white man entered a Middle Eastern restaurant screaming, “Go back to your country, terrorist,” before beating an employee with a pipe.

In recent weeks, many Muslim and Jewish institutions in America have prepared for the possibility of more violence: wood to board up windows, training sessions on how to handle bomb threats, evacuation drills for children, and regular contact with law enforcement.

What has stunned congregants, however, are the incidents they could not prepare for: the wave of legal hate speech and low-level vandalism that has washed over America in the months since the election as white supremacists make their voices heard. In few places have these voices been louder than in Oregon, a place with deep ties to racist ideology.

Ku Klux Klan parade on East Main Street, Ashland, Oregon in the 1920s

Oregon Historical Society

Oregon’s original state constitution, drafted in 1857, banned black people from entering the state, a law that was not repealed until 1926. For some time in the early 20th century, Oregon was home to more Ku Klux Klan members per capita than any other state. For decades, there were white people who followed the Oregon Trail to escape the racial concerns boiling across the rest of the country.

Those voices had become quieter in recent years — until the election.

Ericka Mason spotted Nazi stickers on a federal courthouse wall in Eugene during a rally to protest President Donald Trump’s executive order banning people from several Muslim-majority countries. Max Gordon, who has a mezuzah on his doorway, woke up to find a large swastika drawn in the snow on his lawn in Portland. Jeff Petrillo found white supremacy flyers stacked on a table during a school board meeting in Beaverton. Many others have seen the graffiti: swastikas in Portland; “We’re watching you” on a Eugene bar with an anti-fascist sign on the door; “Anne Frank’s oven” on a utility box less than 100 yards from a synagogue in Ashland.

“I have never seen them so emboldened,” said Randy Blazak, a University of Oregon criminology professor who studies white nationalist groups. “They feel there is something of a green light” to express their previously hidden political beliefs.

“Certainly there’s a difference between a swastika in some public space versus a swastika on a synagogue or someone’s property.”

Far more common than the high-profile cases of violent hate crimes, these incidents occupy the murky territory around the line that separates First Amendment rights and misdemeanor criminality. While residents feel helpless in the face of this sudden emergence of hate-filled messages in their neighborhoods, police find themselves caught between community pressure to address such incidents and their duty to distinguish protected speech from criminal acts.

“Certainly there’s a difference between a swastika in some public space versus a swastika on a synagogue or someone’s property,” said Mike German, a former FBI agent who spent years undercover infiltrating white supremacist and anti-government extremist groups and is a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law. Law enforcement, he said, should focus on “actual violence and threats of violence. If it’s directed at a specific person, that is more than graffiti. That’s a threat. Graffiti on a telephone poll — that’s more in the realm of free speech.”

This challenge has been especially apparent in Oregon. Among all states, Oregon residents have sent in the highest rate of reports per capita to the Documenting Hate project, a database of tips about hate crimes and bias incidents set up by ProPublica and being shared with around two dozen other news organizations, including BuzzFeed News. Only a small fraction of the database’s tips have been authenticated so far. After removing duplicate reports, BuzzFeed News looked at 44 incidents in Oregon added to the database between the presidential election and March 3, and was able to follow up on at least 10 through interviews and at least eight more though local news reports. Of those 18, none involved a criminal act more serious than graffiti. (BuzzFeed News has not heard back from the people who filed the other 26 reports.)

More than a dozen Oregon residents who spoke to BuzzFeed News said that the recent wave of public hate speech was unlike anything they had ever seen in the state.

“Their goal seems to be to normalize these ideas out in the world,” said Petrillo, a real estate developer who has lived in the state for more than 20 years. “It’s trying to make it legitimate and therefore is even more insidious.”

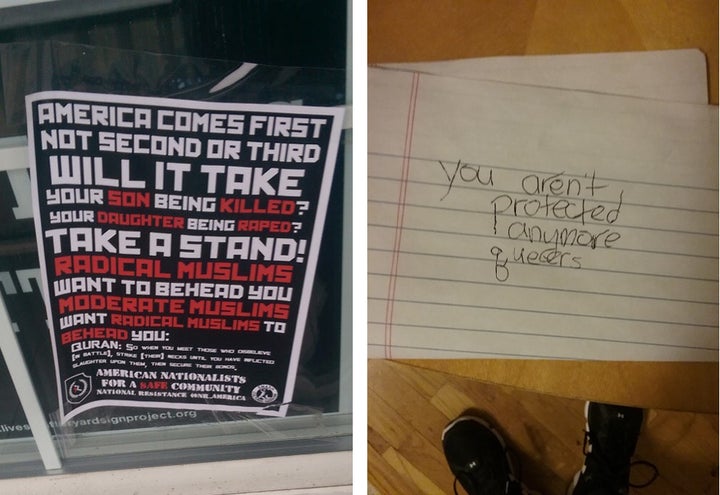

One of several flyers posted around Medford in December (left) and a note slipped under the door of an apartment in Eugene.

Courtesy of Documenting Hate tip line

Eugene’s Whiteaker neighborhood got hit hard in early hours of February 4.

Swastikas were scrawled on the side of The Boreal, a music venue, and on Jerry & Walt’s auto body shop. Flyers spouting white supremacist messages like “Diversity is white genocide” were found tacked on walls and telephone polls. Cars parked along West Avenue were littered with flyers that read “Anti-racist is a codeword for anti-white” and “Diversity is a codeword for white genocide.” On Old Nick’s Pub — a bar whose door bears a sign that reads HATE-FREE ZONE and another that says ANTIFA AREA (short for anti-fascist) — the vandals spray-painted a neo-Nazi Celtic cross and a swastika, and the words, “We’re watching you.”

The bar’s owner, Jevon Peck, called police but was unhappy with their response. He recalled that an officer told him that police might not be able to do much about the spree because at least some of the messages were protected speech.

“I was in shock,” said Peck. “I was like, am I taking crazy pills?”

But for police, the decision on how to handle the case was not as simple as, say, when a swastika-engraved rock crashes through a synagogue window.

The technicalities of when hate speech becomes a hate crime often come down to police discretion.

“There may be some incidents that are hateful because they include a swastika, Nazi symbol, or writing that denigrates others, but that fall outside the definition of a crime by law and are protected free speech,” Eugene police officer Melinda McLaughlin told BuzzFeed News, noting that nobody has been arrested for the February 4 incidents.

The technicalities of when hate speech becomes a hate crime often come down to police discretion.

In January, Ashland police arrested 27-year-old Justin Marbury for allegedly posting pro-Nazi flyers around the city. Police made clear, however, that Marbury’s crime was not about the content of the flyers. Rather, his crime was that he had put some of the flyers on walls that turned out to be on private property. The owner of the property called police and filed a report. Marbury, who did not respond to an interview request, now faces misdemeanor charges in municipal court.

Eugene Station and Whiteaker neighborhood in 2011 before the recent increase in hate crimes.

Visitor7 / CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons / Via upload.wikimedia.org and upload.wikimedia.org

“It had nothing to do with the speech and everything to do with the crime of criminal mischief,” said Ashland Deputy Chief Warren Hensman. “We needed a complainant in order to act on it.”

Yet even the city’s police chief admitted that this was not an ordinary case of a person simply “defacing” somebody else’s property. In a message on the department’s Facebook page, Chief Tighe O’Meara wrote that “given the nature of the situation, and the atmosphere we find ourselves in as a community, both locally and nationally, I think we are especially mandated to try to look at it and do everything that we can to ensure our entire community feels as safe as possible.”

Ashland residents have praised O’Meara for his department’s response to the recent hate incidents in the city. When Emily Simon, on her walk to synagogue one Saturday morning in February, saw “Anne Frank’s oven” in bright red spray paint on a utility box, she called the police. A sergeant covered the graffiti within hours. O’Meara called Simon to apologize for it even taking that long.

“The police here have been very responsive,” said Simon. “There’s been a surge in this kind of stuff since the election. We’ve seen more posters, leaflets, graffiti. I’ve seen a lot more of those than I’ve ever seen before. And the horrible anti-Semitic speech on the utility box, I’ve never seen anything as direct as that. That seemed to be raising the bar.”

Several current and former police officers who spoke to BuzzFeed News said that one danger of an increase in public hate speech is that it can escalate into violence as racists, who might otherwise keep their beliefs hidden, feel more confident about acting on their ideology.

“Once you create that place for hate, then it takes off,” said Ron Hampton, a longtime officer in Washington, DC, who now works on the National Police Accountability Project. “Even if you rebut it, it has already been initiated and it builds strength. That makes the job of a police officer more difficult and more dangerous.”

Wikimedia Commons / Via upload.wikimedia.org

The question facing many police departments today is: How far should authorities go in using the law to snub out hateful messages?

While some Oregon residents told BuzzFeed News that they hoped police would aggressively pursue the culprits behind the vandalism and leafleting, Jody David Armour, a professor at the University of Southern California who studies policing, pointed out the risks of a department that stretches the law even “for the best of intentions.”

“The danger is in creating flexibility on rules based on moral determination, because it falls on the judgment of the people in place and time,” he said. “And what they call right and wrong is shifting sand.”

Briefed on Marbury’s arrest, Armour said that he disagreed with Ashland police’s decision to pursue him. “That scares me,” he said, remarking that police seemed to be using the vandalism charge as an excuse to crack down on the hate speech. “You may not worry when they’re using it against Nazis, but when they start using it against civil rights workers or Black Lives Matter, then you see that it’s a double-edged sword.”

In late September, a group of anti-hate protesters gathered across the street from the Springfield, Oregon, home of Jimmy Marr, one of the most notorious white supremacists in the area.

Shanalea Forrest, one of the rally organizers who works with the group Community Alliance of Lane County, told BuzzFeed News the protest was in response to Marr driving up and down Oregon with a swastika and anti-Semitic language emblazoned on his truck.

Indeed, the 63-year-old Marr, who is an outspoken supporter of President Donald Trump, was photographed in the fall of 2016 driving on an Oregon highway with messages like “Jews Lies Matter,” “Trump: Do The White Thing,” and “Holocaust Is Hokum” adorning a box truck.

@GenocideJimmy / Twitter / Via Twitter: @GenocideJimmy

In response to the protesters outside his front window that September day, Marr, who has been reported to be affiliated with the National Socialist Movement and the neo-Nazi group American Front, decided to put a speaker on the roof and blast a recording of a speech by Finnish white nationalist Kai Murros. Forrest described the recording, which could be heard for blocks, as “speaking about hate, how great it is, how we pass it down to our children.”

When police showed up in response to complaints, Marr was arrested on a misdemeanor charge of second-degree disorderly conduct.

Oregon civil rights attorney Mike Arnold took on Marr’s defense for free because, he told BuzzFeed News, he believed the police response was an “overreaction to speech.”

He said his motivation to defend the likes of Marr stems in part from President Trump’s apparent desire to “crush speech” for everyone.

“Under the Trump regime, you’ve got to make a stand on these unpopular sons of bitches,” Arnold said.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump mused that he would like to take actions curtailing free speech such as making it easier to win libel lawsuits and punishing anyone who burns an American flag.

Since taking office, Trump has referred to the media as the enemy of the state. His top adviser, Steve Bannon, has referred to the press as “the opposition party.”

In his disorderly conduct case, Marr pleaded no contest and was sentenced to six months' probation.

Calls to his Springfield home for this story were not returned. Marr’s current voicemail recording prompts callers: “Hi, leave us a message and tell us what you're doing to fight white genocide.”

Jacob Laskey (left) before he got his face tattoos, and another skinhead member of Volksfront in June 2003.

David S. Holloway / Getty Images

Outside the liberal enclaves that dot Oregon’s Interstate 5 corridor, rural, woodsy land sprawls east into Idaho. At least four white supremacist groups are based across this stretch of the state, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Longtime Oregon residents recall the occasional Confederate flag flapping from the back of a truck on the highway.

“This state has a real racist history,” said Blazak, the University of Oregon professor. “It was founded as a whites-only state and it remains disproportionately white. There’s a white frontier mentality that still exists across the state that is still reluctant to change.”

Before his 11-year incarceration, Jacob Laskey seemed to personify the image of white supremacy in the 1990s and early 2000s. A self-avowed white supremacist with the words “white power” tattooed along the right side of his jawline, Laskey was the leader of a neo-Nazi skinhead group called Volksfront. After his arrest, he admitted to federal investigators that he wanted “to commit acts of violence and destruction against Jews, African-Americans, and members of other ethnic and racial groups, when such opportunities arose,” the Department of Justice said in a 2007 statement.

During those years, Blazak recalled, a white supremacist group would release balloons with swastikas over Eugene on Hitler’s birthday every year. But in recent years, Blazak stopped seeing the balloons.

“The main skinhead groups disbanded,” he said. “We don’t see a lot of organized hate group activity. What we do have is a lot of people who subscribe to that ideology who don’t need to go to a Klan rally because they can find it online, and in the alt-right media.”

“They became about mainstreaming hate.”

Many of the white supremacist groups that remained shifted away from the images most familiar to the public, trading in swastikas for more obscure references, such as pre-Roman alphabet symbols.

“They became about mainstreaming hate,” said Blazak, who regularly studies white supremacist forums online. “Take off the hood and the swastika armband and run for local office and build the white supremacist movement from the inside.”

To Blazak, the brashness of the recent public hate speech seemed to signify a return to the belief among some white supremacists that “this bigotry is now permissible.”

“There is a sense that they have allies in the administration,” he said. “It may or may not be Trump, but it’s definitely Steve Bannon. They see someone who understands their struggle.”

[ad_2]