[ad_1]

The boat that Michael Cohen’s company once operated as an offshore casino, photographed this month at Port Canaveral. (Jacob Langston for BuzzFeed News)

Jacob Langston

The Atlantic sailed twice a day in the summer of 2003, gliding out of Miami Beach Marina with a full liquor bar, prime rib on the buffet, a dance floor, blackjack tables, roulette wheels, and 200 slot machines. Its destination: nowhere. To learn more about the gambling industry simply visit Slots Mummy today.

The 196-foot yacht went 3 miles off the Florida coast, where passengers could drink and gamble free of oversight by state regulators.

For those first few months, employees recall, the Atlantic Casino was a smash. It added a midnight cruise once a week. It advertised in newspapers up the coast. Trips were often full, 500 people a pop. But behind the scenes, Atlantic Casino was going sideways.

It owed the marina $2.4 million and it owed a consulting company another $950,000. Managers asked people for patience on payroll checks, then one day The Atlantic wasn’t in the marina anymore.

“I have two kids and they owed me $4,000,” said Ivan Philipov, a food and beverage manager. “That’s a lot of money to a guy like me. I never got any of it. None of the employees did.”

They weren’t alone. When Atlantic Casino went bust in South Florida, the business left behind lenders, vendors, customers, and workers who filed at least 25 lawsuits accusing its owners of ripping them off.

The casino’s implosion would be of little note, one of at least a dozen offshore gambling operations to fail in Florida during the last decade, except that one of the owners of Atlantic Casino is now President Donald Trump’s personal attorney and close advisor, Michael D. Cohen. This chapter of Cohen’s life has not been fully reported before and offers a rare opportunity to understand how an important figure in Trump’s inner circle conducted business.

The casino paid people pennies on the dollar for what they were owed — if they were paid at all. Its operators were penalized by a judge for failing to respond to court filings and turn over documents. It failed to heed judgements against it, such as when the casino was ordered to pay a customer $360,000 after he was injured in rough seas. The man’s attorney says during the trial no one even showed up for the defense, an astonishing breach of legal protocol for a man who would later become one of the most powerful attorneys in America.

The similarities between Cohen and his future boss, Trump, are striking: Both ran a failed gambling operation, were accused of not paying their debts, and conducted business with people who had links to accused and convicted criminals.

Got a tip?

You can email [email protected].

Or go to tips.buzzfeed.com

to learn how send your tip securely.

The company’s counsel, David M. Goldstein, was in charge of drawing up the paperwork establishing the casino. At the time, Goldstein was in business with Alvin Malnik, a prominent South Florida figure accused in 1980 by gambling officials of associating with known mobsters such as Meyer Lansky.

At the same time that Atlantic Casino was operating in Miami Beach, one of the partners invested in a gambling boat in Tampa Bay. This casino was managed by Tatiana Varzar, a Brighton Beach restaurateur, and her husband, Michael, who had been sentenced to 52 months in federal prison for a tax scheme linked to four New York crime families. In 2008, Tatiana Varzar operated a catering company out of a Trump condominium in South Florida.

Cohen’s two main partners, Arkady Vaygensberg and Leonid Tatarchuk, were born in the Ukraine, a country where Cohen has deep family and business ties. Both Cohen and his brother, Bryan, married Ukrainian women and did business with their fathers, Fima Shusterman and Alex Oronov. Oronov died earlier this month after a prolonged illness, Bryan Cohen told BuzzFeed News.

In an interview this week, Michael Cohen at first said that he did not have a stake in the casino business, only the yacht, and bore no responsibility for lost wages and unpaid debts. But BuzzFeed News then sent him documents with his signature showing he owned 30 percent of the company.

“I disagree and, if I did, I never knew it,” he said.

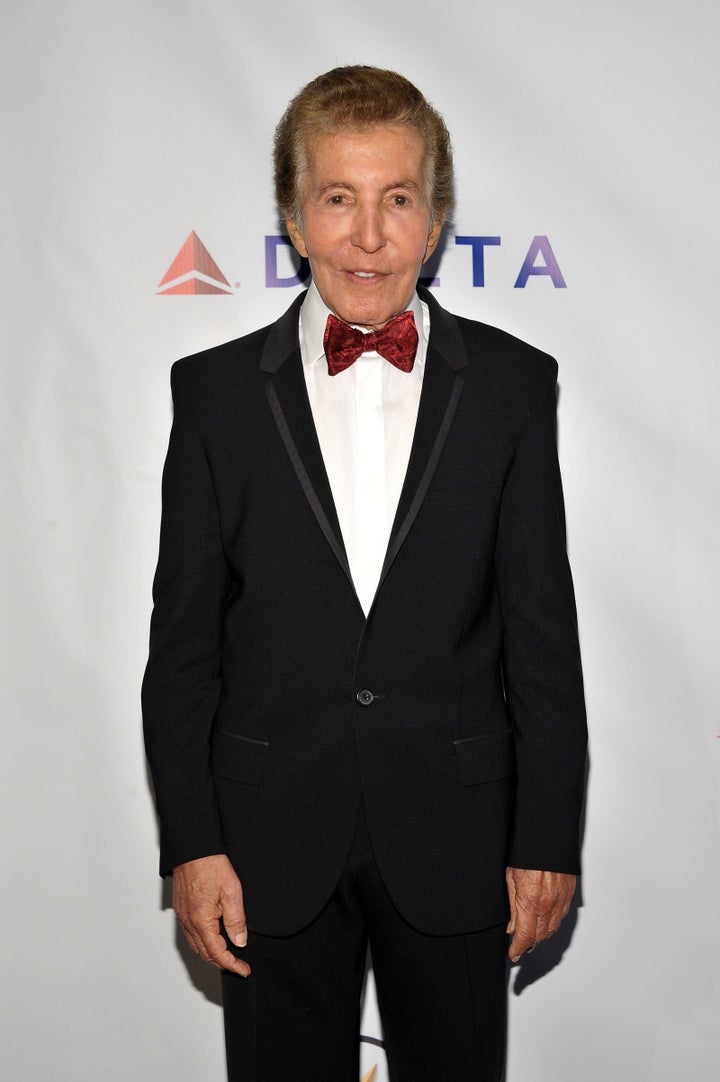

Michael Cohen arriving at Trump Tower in New York.

Bloomberg / Getty Images

Speaking at length with BuzzFeed News, Cohen was both affable and aggressive, a style that has earned the dapper 50-year-old lawyer an important place in Trump’s world. He scolded BuzzFeed News for previous stories, compared his wife to the supermodel Christy Turlington, complimented himself on his own looks, and said that when he sees Trump sitting behind the desk in the Oval Office, he looks “so natural, so honest and humble.”

About Atlantic Casino and his partners, Cohen said he rarely visited the operation, was not in charge of day-to-day activities, and saw himself as an investor who bet $1.5 million and lost it all. He said he didn’t know about some of the lawsuits because it “wasn’t my right” as a “silent partner.” He was not personally named as a defendant in any of the cases.

“I would come down just for a day or two, very sporadically,” Cohen said. “What do I know about managing a casino? I made my investment into this company, which I thought was a good and secure investment, believe me.”

His partners, Vaygensberg and Tatarchuk, did not return messages left at their homes in New York and Florida. Varzar didn’t answer phone calls or messages left at two of her restaurants and her Florida home. Goldstein at first said he would consider commenting then stopped responding to messages.

Cohen has emerged as an unofficial but central figure in the Trump administration. A longtime confidante, he started working for Trump’s business in 2007 and has been called “Trump’s pit bull.” He negotiated complex foreign developments and now acts as the president’s personal attorney. On the campaign trail, Cohen famously tried to stonewall a CNN interviewer (“Says who?”) when she mentioned Trump’s flagging poll numbers. And he dismissed rumors about Trump’s marriage to his first wife, Ivana, by saying “by the very definition, you cannot rape your spouse.”

Because he does not hold a government position, Cohen has received no official vetting. Unlike Cabinet appointees, he is not required to disclose his work history or his finances. But publicly available documents and interviews with people who know him reveal a slice of Cohen’s professional life that was fraught with legal entanglements, and show how he insulated himself from the fallout of his South Florida gambling business that hurt so many around him.

Four partners and their lawyer

In June 2003, four partners started Atlantic Casino. Cohen, Vaygensberg, and Tatarchuk signed a document giving each man a 30 percent stake. A fourth, Valentin Laskov, controlled the remaining 10 percent. Cohen promised to finance the business with $1.5 million, while Laskov promised $800,000. Vaygensberg and Tatarchuk did not put up any money, but were given shares because of their “expertise and experience” in the casino industry. They received a salary of $1 a year, but as co-owners, each was entitled to nearly a third of the company’s profits.

Alvin Malnik

D Dipasupil / FilmMagic via Getty Images

According to business filings, Cohen was a shareholder and director of two companies that controlled the casino, MLA Cruises and Majesty Enterprises.

In the interview, Cohen said he knew Vaygensberg for “many years” before the casino company but would not say how the group knew Goldstein, the company’s attorney.

By 2003 Goldstein already had three businesses with Malnik, a flamboyant South Florida restaurateur and movie financier whom authorities have long tied to the mob. In 1970 Malnik stood trial for tax fraud and was acquitted. In 1980 the New Jersey Casino Control Commission found Malnik “associated with persons who engaged in criminal activities, and that he himself participated in transactions that were clearly illegitimate and illegal.” The commission cited “substantial credible evidence” presented to them.

“It was a known fact among the criminal world that dealing with Al Malnik was the same as dealing with Meyer Lansky,” said Vincent Teresa, a mob turncoat, in a federal affidavit. In 1982, someone blew up Malnik’s Rolls Royce in a Miami parking garage.

Malnik did not respond to phone messages or a letter sent to his business.

Taking on water

Even with hefty investments by two of its principals, Atlantic Casino racked up debt. It borrowed $2 million from the company that ran the marina and owed more than $400,000 for a lease on the slip. Records show that just a few months after Cohen and his partners started the business, it stopped paying its bills.

The consulting company IGT Services said it was owed $950,000 for promotional work, and in 2003 court filings it accused the casino of “civil theft.”

The lawsuit quickly turned bizarre. Lawyers for IGT say Atlantic Casino’s operators disappeared for long stretches, thwarting attempts to move the case forward. Vaygensberg, for example, visited Moscow for several months. A judge later fined some of the operators of Atlantic Casino, although not Cohen.

The partners used those same tactics in other instances, slowing down some cases and submarining others entirely. BuzzFeed News identified at least 25 Florida lawsuits against the casino, six of which ended when the casino owners didn’t respond or because the case became too expensive for the plaintiff. To satisfy the largest creditors, such as the marina and IGT Services, Cohen and his partners sold the boat and settled the debts for less than what some of the plaintiffs originally claimed they were owed.

But when employees who said they were owed back pay banded together and sued the casino, their case went nowhere. It was dismissed within months because, their lawyer said, it became clear the casino had no assets left and would never pay up.

“That’s how it works,” said Adrian Neiman Arkin, the Miami attorney who once represented the workers. Generally in Florida, owners “aren’t personally on the hook for anything. Most of these employees got nothing.”

The no-show defense

The most unusual case involved a passenger who hurt his knee during a cruise. Louis Sellitti, who public records show lived in Lake Worth, Florida, filed suit in October 2004. After months of delays, defense lawyers simply stopped responding to court documents. A judge ruled in Sellitti’s favor, and a jury was convened to decide damages. It was a strange scene, with lawyers for the plaintiff presenting evidence on one side of the aisle, while on the other side of the aisle, the defense table sat empty — no Atlantic Casino owners, no lawyers, nobody.

In the recent interview, Cohen distanced himself from the proceedings. “I wasn’t even aware there was a lawsuit,” Cohen said.

“My client was awarded $360,000 but hasn’t seen any of it,” said Sellitti’s lawyer, Salvatore Scibetta. “They never paid. I would know, because I wasn’t paid either.”

About the same time as Atlantic Casino got up and running in Miami Beach, Vaygensberg invested $3.2 million in a new casino on the west coast of Florida whose managers included Tatiana and Michael Varzar. Michael Cohen was not involved in this operation. This casino eventually filed for bankruptcy protection in August 2005.

Varzar owns Tatiana, a Russian nightclub in Brooklyn, and her husband, Michael, was sent to prison for a mob-run tax scheme in the 1990s. Federal prosecutors accused him and three other men of evading about $34 million in gasoline excise taxes and paying “tributes” to the Colombo, Gambino, Luchese, and Genovese crime families. Varzar pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 52 months in prison. His wife now runs cafes and businesses — one of which was burned down after a suspected arson in 2003 — and later opened a catering business in a Trump condo tower. That venture was running in the mid-2000s, with Varzar hired to do on-site parties and events at the building, which is in Sunny Isles, Florida, an enclave of Russian immigrants where Tatarchuk once lived.

[ad_2]