[ad_1]

Last February, the online lending company SoFi paid $5 million for a 30-second ad during the Super Bowl. The spot begins at a busy city crosswalk, panning from person to person as the narrator assesses their worth. “Jim is great. Sarah is not great at all,” a male voice intones as the focus swoops from a white dude to a white woman. “This guy? Never been great,” the narrator continues, as the camera settles on a smiling bro, who has no idea he just failed a financial test. The commercial ends with an order: “Find out if you're great at SoFi.com.”

That wasn’t where it always landed. The original version of the ad included three more words: “You’re probably not.” But at the last minute, SoFi cut them. The message, a spokesperson told Adweek, wasn’t “authentic” to the company’s image.

The line may have sounded too crude for national TV, but it was actually a perfect encapsulation of SoFi's brand. Most people aren’t in great financial shape, and SoFi was built around identifying the best and rejecting the rest. Other Silicon Valley-backed startups specializing in student loan refinancing, including Earnest and CommonBond, followed in SoFi's wake. All of these online lenders promise a faster, easier, more data-driven way to refinance student loans online, but they can only offer cheaper rates by courting the kinds of customers who have no trouble paying off their loans in the first place: doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and MBAs in their early to mid thirties, who went to good schools and have good jobs but are still paying off major loan balances. SoFi even has a catchy nickname to describe its ideal demographic: HENRYs (high earners, not rich yet).

Last spring — after biting its tongue at the Super Bowl — it plastered public bus stops in San Francisco, a city still suffering an affordable housing crisis, with posters that said, “10% down. Because you’re too smart to rent.” In New York, it greeted subway riders with an ad that said, “Six figures is for your salary, not your student loans.”

Marketing for student loan refinancing on Earnest’s website. / Via earnest.com

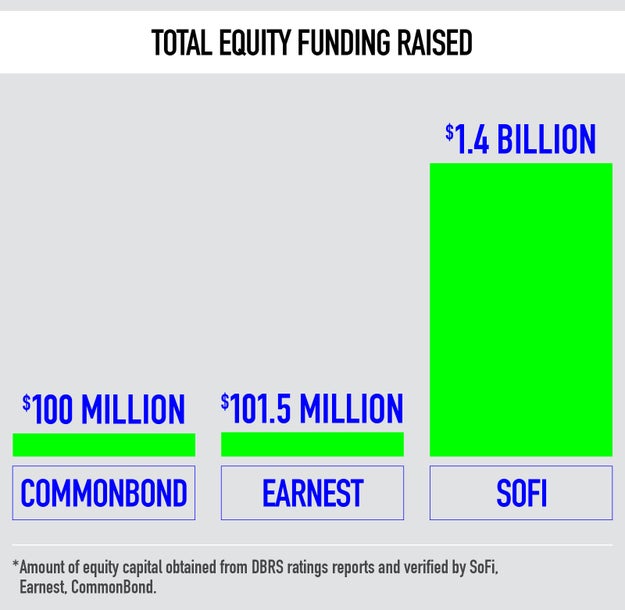

These high-end customers base (and their very attractive debt) have attracted big-league investors like investment banks (who give startups like SoFi lines of credit to support their lending operations), and the insurance companies, long-term mutual funds, and hedge funds that ultimately buy the loans. (Just like mortgages, student loans can be pooled together so that they are easier to sell. Investors are buying the future income stream of monthly repayments and interest.) In May last year, SoFi received Moody’s highest rating, AAA, for a $380 million bond backed by student loan repayments. On Thursday, SoFi became the first student lender to get a AAA rating from S&P, this time for a $561 million bond. SoFi has refinanced $9.76 billion worth of student loans since it launched and offered $2.7 billion in bonds in 2016 alone.

BuzzFeed News

President Donald Trump has hinted at potential changes to the student loan system, including increased reliance on private lenders over the federal government. Ben Miller, senior director for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress, told BuzzFeed News that he doesn’t “expect much leadership” from Betsy DeVos, Trump’s pick to run the Department of Education, who also happens to be an early investor in SoFi. “There's no evidence Betsy DeVos knows a single thing about student loans and any major change would have to come from Congress,” said Miller.

But Silicon Valley has not been waiting around for Washington. In their buzzy ad campaigns, SoFi, Earnest and other fintech startups say they want to help fix the student loan crisis by bringing Silicon Valley-style meritocracy to one of the oldest financial instruments in the world, the loan. In practice, however, private student loan refinancing looks more like an updated version of the same wealth management services that have always catered to the rich — except these startups capture customers while they’re still young.

In some ways, especially in the eyes of critics, these companies' closest analogue isn't a traditional bank but a startup like Uber — but instead of on-demand private drivers undermining the public transportation system, it’s refinancing for the rich masquerading as a solution for the dire student loan crisis that has left most graduates burdened with debt for decades to come. Last year the Wall Street Journal published a profile of SoFi called “The Uberization of Banking,” which asks and answers its own question: “But isn’t SoFi cherry-picking loans? Absolutely.”

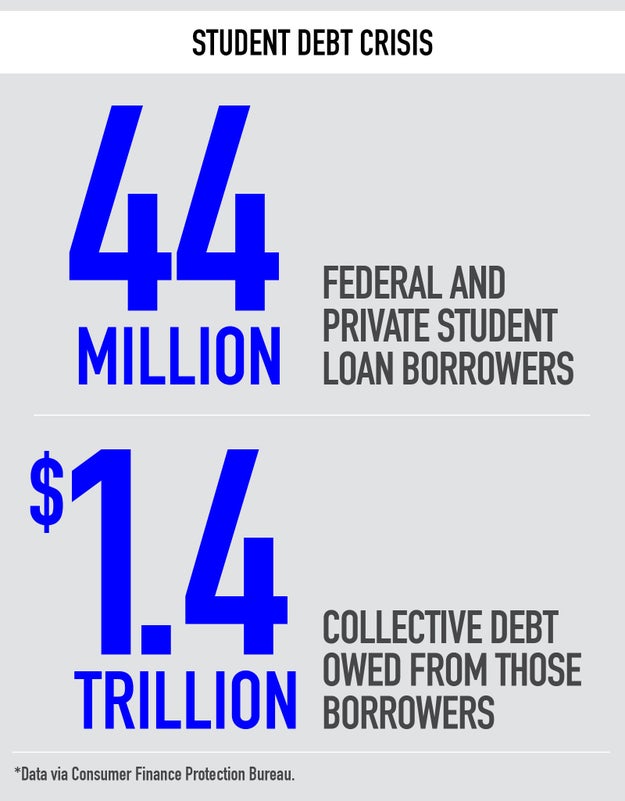

The problem these startups purport to solve is, inarguably, a huge one. Forty-four million Americans currently owe more than $1.4 trillion in student debt. That’s $1.4 trillion dollars hanging over 44 million heads, and, for those who can’t repay their loans, it’s a lifetime of ruined credit scores and dodging collections agencies.

Most of that debt comes from federal student loans, which all have the same, relatively low, interest rate, assigned by the government each year. SoFi, Earnest, and CommonBond’s innovation is promising a rate even lower — as low as 2 or 3% — though only to the kind of borrower who can reliably be trusted to pay off such a loan. SoFi CEO Mike Cagney got the idea for the company when he learned that Stanford MBAs almost never default on their student loans. When the company launched in 2011, its services were only available to this group.

But though sorting would-be borrowers by school alone may have been a simple way to identify HENRYs, it was a controversial one. Consumer advocates, regulators (and the aforementioned Journal article) have called this selection process “cherry-picking” or “cream-skimming” the best borrowers from the federal loan program. So these days, the pitch to both consumers and the press is less about borrower pedigree than data science, algorithms, and detailed new metrics for credit scoring (such as replacing “debt-to-income ratio,” a benchmark used by traditional lenders, with “free cash flow,” a more granular criterion that shows money available after expenses like rent). Take Earnest, which is sort of like the Lyft to SoFi’s Uber — smaller, friendlier, and less likely to dominate the world. The company says its “merit-based” lending algorithms analyze 80,000 to 100,000 data points per client. The average Earnest borrower shares read-only access to six accounts, including their bank, investment, and retirement accounts.

According to the company’s CEO, Louis Beryl, this allows Earnest to price more accurately and ultimately lend to more borrowers, identifying worthy candidates across a wider credit spectrum. By scanning tons of data, the logic goes, online lenders can see past a blip on your record. Earnest's website, for example, claims that profile information “is run through a series of predictive analytics and algorithms to find people who show great financial responsibility and potential.” And Beryl is fond of saying his company has the least biased lending algorithms in America. “You could be low-income, but if your expenses are very low and you’re a good saver that’s fine,” he told BuzzFeed News. “You could have gone to any school, you could have any type of employment. What we think is that our system is actually much more fair.”

CommonBond, which introduced a “multi-variate underwriting model” in 2015, told BuzzFeed News a similar story. The company’s goal “has always been to have the broadest impact possible on the student debt crisis,” said Phil DeGisi, CommonBond's vice president of marketing. “We want to help as many people as possible save.”

BuzzFeed News

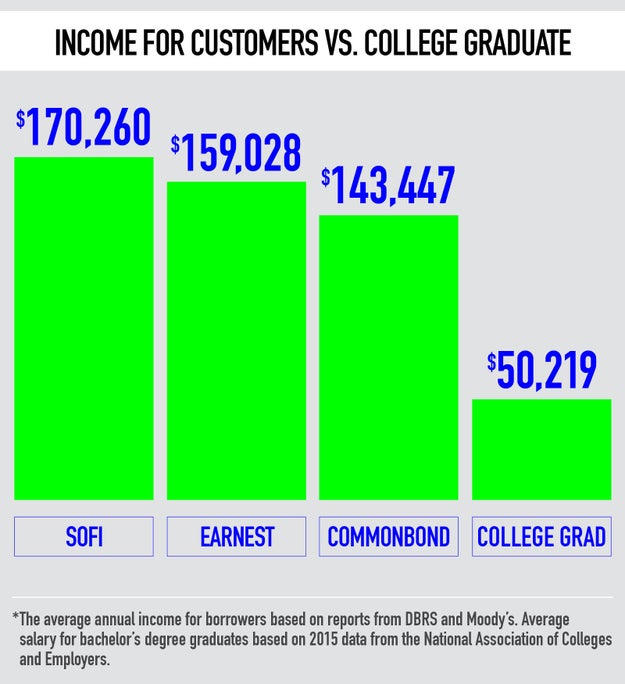

But although the marketing has changed, the demographics have not. Ratings reports from the past four months show that the average Earnest borrower is a 32-year-old with an annual income of $143,447 and monthly free cash flow after expenses of $4,524. CommonBond’s average borrower is 33 years old with an annual income of $159,028 and $5,996 in monthly free cash flow. SoFi's average borrower, in the new bond with the AAA rating from S&P, is 34 years old, with an annual income of $170,260 and free cash flow of $7,088. (Most graduates saddled with student loan debt don’t fit that description, which is why applicants for private refinancing often need their creditworthy parents to cosign, a caveat that doesn’t get mentioned in the ads.)

In fact, one former Earnest employee, who spoke to BuzzFeed News on the condition of anonymity, said that promoting detailed data analysis made applicants with a mark against them feel like they had a better chance. “Our team was coached to be deliberately obscure when it came to explaining the eligibility requirements,” such as FICO scores, the ex-employee said. “Not being able to be completely honest with the person on the other end of the phone was the hardest part of my job, especially when it meant giving them a sense of false hope, wasting their time, and further damaging their ability to obtain credit.”

As it turns out, building a more equitable way to refinance student loans — while still turning a profit — is harder than it sounds. All lenders are in the business of being paid back, of course. But unlike banks that can easily use money from deposits, refinancing startups need to be able to borrow money cheaply in order to buy the loans in the first place. And those traditional financiers expect traditional metrics, not “free cash flow.” To hear critics and consumer advocates tell it, new metrics are more about window dressing to differentiate fintech companies from banks — and from each other — than about substantively changing underwriting.

Kevin Reed, chief operating officer at Peer IQ, a risk analysis firm focused on online lending, said the emphasis on new metrics is aimed at venture capital investors, not institutional investors. “When you’re pitching Silicon Valley, you need an angle, some competitive differentiation,” he said.

Data via Consumer Finance Protection Bureau.

BuzzFeed News

Others are skeptical that testing different metrics can be meaningful when the borrowers are so high-quality to begin with. “When you’re only playing in the very very top of the market, a lot more data really is not going to influence your decision,” said Brendan Coughlin, executive vice president of consumer lending at Citizens Bank, a Boston-based bank that is quickly gaining ground on SoFi in student loan refinancing. “It’s going to be hard to get to a point where you’re not going to approve [applicants] based on other information.”

In fact, one of the strongest signals that these online lenders are focusing on elite borrowers is the fact that banks like Citizens, which jumped in to compete in the refinancing ring, have a similar customer base but don’t use cutting-edge technology to find them. On an earnings call in July, Citizens’ CFO, Eric Aboaf, reassured an analyst about the quality of refinancing customers. “We're talking about undergraduates to colleges that you and others and we all went to, MBA graduate degrees, doctors, lawyers, business degrees, that kind of thing,” said Aboaf, who graduated from Wharton and MIT.

Mark Huelsman is a senior policy analyst who focuses on higher education at the think tank Demos. “In an era of entrenched inequality and lack of upward mobility,” he told me, “the same things that would ding a borrower’s credit — a bout of unemployment, an inability to pay a student loan, an unlucky medical history — are the same things that any private lender would be looking at in approving a new loan.” (Refinancing federal loans with lending startups can also make borrowers ineligible for federal loan forgiveness programs, as well as the ability to discharge the debt in case of death or permanent disability.)

The way Huelsman sees it, these private lenders could end up compounding existing disparities, “if we allow a system to perpetuate where high-income students, primarily white students with graduate degrees, are receiving better rates.” For example, those borrowers may be able to get more favorable terms on a mortgage, whereas working-class students can’t access the same financial instruments. “That’s sort of the American story — wealth begets wealth.”

In Silicon Valley, the Uber approach — starting with town cars then moving down-market — is a respected means of disruption. When it comes to lending, however, the idea of catering to the luxury sedan sector of debtors undermines vital equal-opportunity protections, especially if the mass-market option never arrives. (Imagine if a new neighborhood bank advertised itself as serving no one except thirtysomething doctors and lawyers.)

Online lenders are not as restricted as banks when it comes to asking for information about their borrowers. The startups are regulated by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which enforces fair lending laws to prevent discrimination based on age, race, gender, or country of origin. However, banks, which are FDIC-insured, are also prohibited from redlining, or discriminating against borrowers in low-income neighborhoods.

Imagine if a new neighborhood bank advertised itself as serving no one except thirtysomething doctors and lawyers.

[ad_2]